Chardonnay is one of the most divisive wines in the world. It's also the most popular. Naturally, when you're the most popular of anything, you attract a lot of people on both sides of the fence. Maybe you love it, maybe you hate it, and maybe you just haven't tried the right one. This versatile grape is the chameleon of varietals, possessing a putty-like malleability that allows it to take on a huge range of wine styles.

From Old World to New World

Chardonnay ripening on the vine in Carneros.

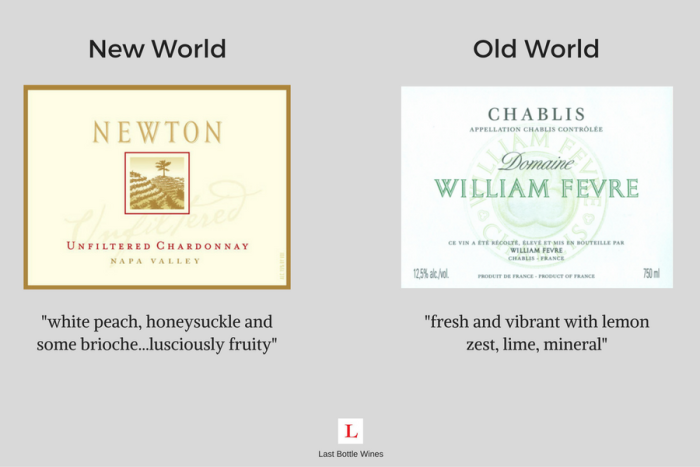

Chardonnay originally came from France, specifically Burgundy, where a cooler climate, rugged limestone soil, and traditional winemaking approach often lead to a more austere Old World style of wine. White Burgundy tends to be lighter in color with pronounced notes of citrus, white flowers, spices, minerality, and racy acidity. From its ascent in Burgundy, Chardonnay then became a fixture in Champagne, where it's one of the three principal grapes used to produce the world famous sparkling wine.

Then you have the New World approach, or what some might call California-style Chardonnay. Warmer weather guides Chardonnay toward a different expression, where it's usually darker yellow in color with ripe tropical fruit flavors, thick texture, and less acidity. Brands like Rombauer push the limits of this type of Chard with their super-rich, buttery style that most wine drinks either love or hate. Geography isn't the only factor in determining if a Chardonnay fits the Old or New World mold. There's no one-size-fits-all approach you can apply to Chardonnay from any single region; each style is guided by weather and climate as well as by the winemaker's decisions.

Some winemakers stand firm in their belief that the Old World approach shines light on the purity of Chardonnay, while others believe their New World style amplifies the fruit's character. Others bridge the gap between both styles. Neighboring producers in Sonoma or Chablis can produce vastly different Chardonnay wines using the same exact grapes depending on the winemaking decisions.

How Oak Shapes Chardonnay

By itself, Chardonnay has a fairly neutral flavor. When it comes into contact with oak, a lot can happen. Oak's dramatic impact on Chardonnay can include many results:

- Imparting rich flavors of vanilla, butterscotch, crème brûlée, and caramel

- Developing richer, more hedonistic flavors as the wine spends more time in contact with the wood

- Yielding a deeper color from natural oxidation

Some winemakers blend various lots in different types of oak, mixing new and used oak barrels or alternating toast levels then working toward a final master blend. They don't call oak the winemaker's "spice rack" for nothing.

The Unoaked Disciples

Chablis normally shows very little oak influence, favoring crispness and acidity over ripeness.

Whether by tradition or just personal preference, some winemakers don't use any oak. They might choose to ferment in stainless steel or concrete eggs instead. Their unoaked Chardonnay stands out as a pure expression of the grape. Unoaked Chardonnay isn't always crisp and racy, though. If the winemaker introduces malolactic fermentation or keeps the juice fermenting on lees, the texture and flavor can change dramatically.

Where's the Butter?

Let's talk about the ubiquitous buttery note you find slathered all over some Chard. It probably the most polarizing aspect of Chardonnay.

Jam Cellars know exactly what their customers want.

This buttery flavor is a byproduct of a process called malolactic fermentation. Some of the effects of malolactic fermentation include:

- Giving the wine a softness, a sort of oily texture

- Creating the buttery note (some) people love along with some secondary notes of hazelnut or baked bread

- Raising the pH, making the wine less acidic

Wine contains a lot of acids, one of which is malic acid. This gives wine a green apple taste, which is especially notable in Chablis wines. If a winemaker decides to add certain bacteria into the mix, malic acid turns into lactic acid. When this happens, another byproduct called diacetyl is produced, which tastes just like butter.

Sometimes you'll read that a wine has undergone 30% ML (malolactic fermentation) and was aged in neutral oak barrels. Others might go full 100% ML. Just like oak, the amount of "malo" depends on the winemaker's preference. Some feel it brings a perfect harmony of flavor between the oak influence and Chardonnay's natural profile. The biggest butter bombs combine 100% malolactic and lots of new oak.

Aging "Sur Lie" Adds Texture and Complexity

There's one more winemaking decision important in shaping Chardonnay. Lees include dead yeast cells and other sediment that falls to the bottom of the barrel or tank during fermentation. As these break down, all sorts of amino acids, proteins and other little flavor shaping compounds release. Some winemakers like to stir the lees, a process called bâtonnage. As the lees come into contact with the wine, it imparts subtle flavors and a creamy mouthfeel texture into the wine.

Serious collectors know there's nothing quite like a well-aged Meursault or Chablis. High-acid wines tend to age better too, which is one reason most of the highly regarded examples come from Burgundy, where the wines have naturally higher acidity. Of course you can still age a good California Chardonnay ten years or more. Over time, the secondary and tertiary aromas and flavors develop, and the color deepens into a darker yellow.

Chardonnay is the most widely planted wine grape variety globally, and few other grapes have such a broad range of styles. If you're part of the "ABC" (anything but Chardonnay) crowd, perhaps you just haven't tried the right style of Chardonnay yet.